Behavioral Investing: EMH, AMH, Bubbles and Finance 3.0

- Adaptive Alph

- Feb 8, 2020

- 8 min read

Chicago After 1929:

Pretend that you are at the most amazing cocktail party in Chicago in the early 1930s. Al Capone has provided the illegal booze so that everybody is drunk and happy. All of the guests are aspiring investors so they enjoy talking about the markets and you tell other guests that a market is defined by the nature of its participants. Arguing that the market is driven by human emotion would probably not lead to disagreement among the guests. However, if a guest asked you what the implications of an emotionally driven market is on asset prices then odds are that you might not have a great explanation. It stems from the fact that behavioral finance is the first field of study seeking to answer such a question and the theory itself was not developed until the late 1970s by the distinguished University of Rochester contradictionista (economist), Richard Thaler[1]. Per its definition in the dictionary, behavioral finance is a theory that combines psychology and economics to explain how irrational human decision making impact markets and create anomalies in asset prices. If you understood the theory behind behavioral finance before or even after the great depression in the early 1930s, gangsta Capone would with 100 percent likelihood provided you with free booze at this party as your unique understanding about what drives and pops bubbles would generate a high return for Capone’s portfolio ceteris paribus. Reading this will therefore make you an excellent cocktail party guest and my hope is that, in the future, you will enlighten a crowd to get free booze.

Dominate the cocktail party!

Sensitive Shiller and Sir Greg: Behavioral vs Traditional

The two leading financial theories is traditional and behavioral finance. Let us explain the difference between them using an example. At this 1930’s cocktail party, you first run into selfish Sir Greg, a traditional finance investor who is very rich and knows everything about the market. He also brags that his investment style maximizes his own and his clients’ utility. As a traditional investor, maximizing utility equals making as much money as possible through optimizing returns. Sir Greg then states that all his decisions are rational and that he avoids taking unnecessary risks. When another guest asks Sir Greg what he does for a living, he answers that he used to be a stock broker and that his business went bankrupt as a result of the great crash in 1929, which explains why he is currently looking for new clients. Standing next to Sir Greg, quietly, is Sensitive Shiller who has cautiously been thinking about whether or not to jump into the conversation with Sir Greg. Shiller’s reason for not joining the conversation is that he fears being made fun of rather than being praised for his opinion. Sensitive Shiller also works as a stock broker, but he understands his behavioral limitations and therefore tailors his client portfolios more to the behaviors of the client rather than to just optimizing return. Ultimately, Sensitive Shiller overcomes his fear and takes a leap into the conversation calmly explaining that he retained almost all his clients despite the great crash. Sir Greg enviously asks Shiller how he pulled it off and Shiller answers with one word - treasuries. Shiller models his portfolio like traditional investors by using quantitative measures such as expected return, variance and correlation, however, he also models qualitative measures of his clients to account for human nature. A common way to account for human nature is to use a layered portfolio approach by dividing up the client’s portfolio to meet 3 separate objectives. The first objective is generally to maintain the standard of living, the second tends to increase wealth slightly and the third increases wealth substantially. A layered portfolio approach signifies a behavioral investor and is a major reason for why Sensitive Shiller retained his clients. Shiller most likely over allocated money to the first objective by investing in treasuries, while Sir Greg focused mostly on goal 2 (equities) and 3 (risky equities).

Andrew Lo - the father of the Adaptive Market Hypothesis

Andrew Lo's AMH Revolution

A driving influence guiding Sir Greg and Sensitive Shiller is the efficient market hypothesis (EMH). Many people have heard the story about two economists walking down the road and the first economist spots a USB loaded with a bitcoin on the ground. The first economist then reaches for the bitcoin meanwhile the second economist utters, “If that bitcoin was real someone else would already have picked it up and that bitcoin must therefore be worthless”. According to EMH, there is no edge in investing or picking up free “bitcoins” as prices already reflect all available information. If that was the case then the traditional finance investor has an advantage, as the optimized portfolio should outperform a behavioral portfolio. However, opinion of economists follow a uniform distribution and this explains the inability to reach consensus about whether the market is efficient. The logic of EMH is that the more efficient the market, the more random is the price sequence generated by such a market and the more difficult the market is to forecast. If you analyze the market today, you can see that it is difficult to predict if prices will go up or down tomorrow even with the use of computers. However, Andrew Lo, a fellow more distinguished PHD contradictionista from Harvard University, developed a theory complementing the EMH based on behavioral assumptions under the name adaptive market hypothesis (AMH). Lo’s theory tests the foundation of EMH by using behavioral assumptions to poke holes in the EMH. If the market follows the AMH then one can conclude that human behavior will create predictable patterns in the market and investment practitioners using advanced unemotional methods, such as machine learning, can generate Adaptive Alpha. These market patterns can result from behaviors unknown to experts or from the following:

Herding behavior is a bias making individuals follow the “pack”. For example, it is a status symbol to have the latest iPhone, which in turn drives up the price of the iPhone to irrational highs, even though there are substitute phones that are equally good at a much lower price. This happens in the market all the time. The price of bitcoin, marijuana stocks and tulips in the 1700s are just a few examples.

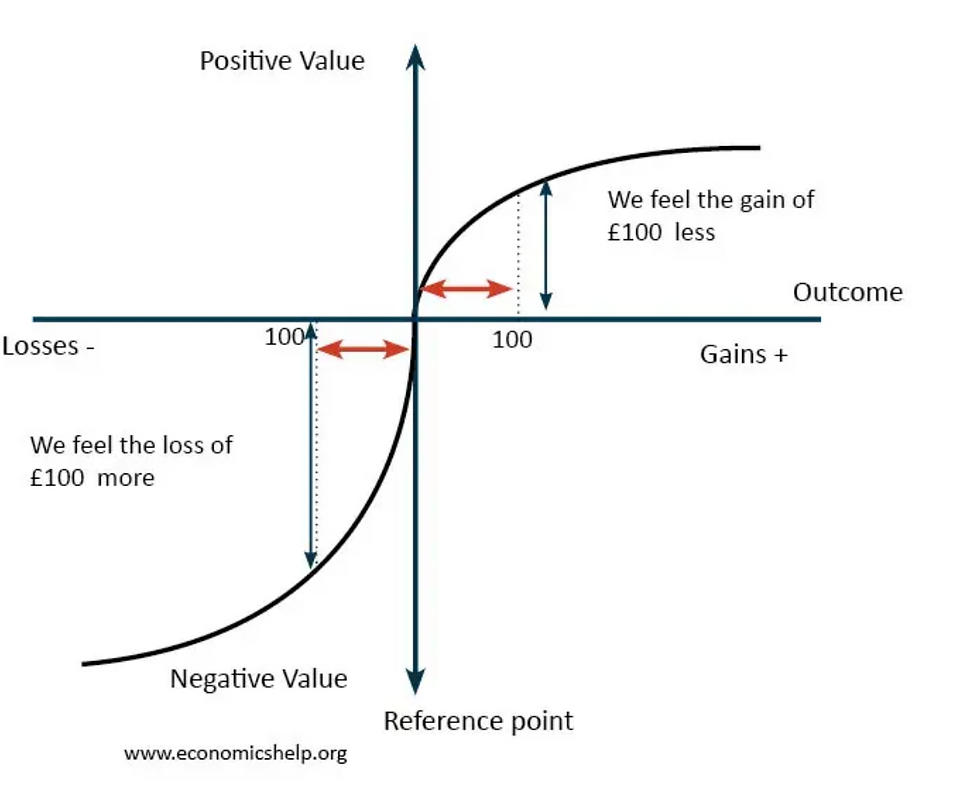

Prospect Theory is a loss aversion bias that demonstrates how people respond differently to the prospect of losing and winning money. The prospect theory states that people are risk seeking and willing to gamble when there is a certainty of losing money. However, if there is a certainty of winning money then people are instead risk averse. This is best illustrated by an example. The expected return between winning 100 KUSD with certainty or 1 million USD with a 10% probability is the same at 100 KUSD. Most people would then choose to get a 100 KUSD with certainty. If you flip the experiment so that one will lose a 100 KUSD with certainty or have a 10% probability of losing a 1 million USD, then most people would choose to gamble. This difference in preference is dependent on how people emotionally respond to gains and losses. This type of behavior drive the markets away from the efficient price.

The Gamblers fallacy bias is a behavioral bias existing because gamblers incorrectly believe that a past event makes a future event more likely even though these two events are mutually exclusive. A classic example of a gambler’s logic is the “this time is different”. A gambler would play the slot machine just one more time if the gambler has lost money on the past 10 tries. However, the odds of winning money playing slot machines at any given try does not increase with additional rounds – the rounds are independent! In financial markets, the gamblers fallacy can lead to investors holding on to stocks that have dropped massively in value because they hope that the stock price will revert to the mean.

Prospect Theory - we feel winner differently from losers

Tech Bubble

Biased decision making have been thoroughly tested by numerous psychologists and economists such as Kahneman, Shefrin and Thaler. If we look at Sir Greg in the earlier example, he clearly suffers from gamblers fallacy, herding behavior and loss aversion bias. He suffers from gamblers fallacy and loss aversion because he held on to all his clients’ investments during the great crash hoping that it would revert back to the mean and from herding behavior as he, like most other investors in during the roaring 20s, put all his money into the stock market. The key in the previous sentence is “most other investors” because if it is possible to forecast that other investors suffer from emotional biases then it might be possible to forecast how any given event could drive the market away from its efficient price. The tricky part is that the cause and effect link between the event and market price outcome is none-linear. In Robert Shiller’s book, irrational exuberance, he outlines more than 12 different behavioral causes explaining the tech bubble in early 2000 and 3 of them are outlined below[2].

The internet boom resulted in online trading. In 1997 there was 3.7 million online account in the U.S. and by end of 1999 there was more than 9.7 million accounts. This encourages market participants to trade more frequently and thus exert their behavioral biases on the market.

The decline of inflation and the effects of money illusion. Inflation is measured as a change in the consumer price index and Shiller noticed in his research that people pay attention to inflation. Low inflation can boost stock market prices as the public considers a low level of inflation as a sign of a strong economy. Worth noting is that during the period 2008-2018, the federal reserve has inflated the market through quantitative easing to prevent deflation and market valuations have reached record high.

Expansion of defined contribution plans have forced individuals that previously was not investors to learn more about the markets and accept stock market investments as a viable strategy. Increasing the familiarity with stocks encourages investing.

Yale Contradictionista - Robert Shiller

Bubbles and Finance 3.0: AI

Behavioral bubbles repeat themselves, but the cause of each specific bubble is more of an historical rime than a repeat. The above three bullets as outlined by Robert Shiller partially explains the dotcom bubble in the early 2000s and might also explain the bubble currently expanding in the 2020s. Obviously there are more than 12 variables, as Robert Shiller described in his book, “Irrational Exuberance”, impacting asset prices. Note also that for any behavioral bias causing investors to push the price of an asset up there is potentially a behavioral bias working in the opposite direction. This means that the cause effect relationship between investors and events takes place in a multi-dimensional space that humans are unable to visualize. What makes the relationship even more difficult to visualize is that the cause effect relationship is dynamic because the market is constantly evolving. Thus, the next generation of Sensitive Shillers must rely on computing power and statistical techniques to extract information from data to empirically model how collective human behavior impact market prices. Thanks to Moore’s law, computers are now powerful enough to solve complex problems such as self-driving cars, facial recognition and investing. We can therefore define a successful investor in finance 3.0 as one who provides the computer with an optimal framework of the game (the market) combined with the objective to outperform the returns generated by the market. This is synonymous to the definition of machine learning, which is the ability to automatically learn and improve from available data, instead of following static, explicitly programmed instructions.

Dotcom bubble - notice the current/2018 market valuation

Conclusion

In this blog, Adaptive Alph described the difference between traditional and behavioral finance through selfish Sir Greg and Sensitive Shiller. In addition, he explained the efficient and adaptive market hypothesis. Finally, he described how human behavioral biases cause predictable patterns and bubbles, which could make a finance 3.0 technique, such as machine learning, a profitable strategy.

You finished, Well Done!

Always Adaptive!

[1] The term “contradictionista” stems from the well-known fact among economists that the opinions of economists follows the uniform distribution

[2] Page 51 irrational exuberance Robert shiller

Comments